[nextpage title=”Introduction”]

Here you will learn about trends in the intercultural field, which will help you

- anticipate people’s responses to the topic of ‘culture’ and ‘intercultural competences’,

- have a clearer frame of reference when discussing the topic,

- have a more informed conversation with your clients, and anticipate their interest and needs,

- satisfy your curiosity about this important subject.

We have identified the following four trends:

- From cross-border business interactions to interactions within culturally diverse societies,

- From stand-alone intercultural trainings to ‘culture’ / intercultural competence being part of a more complex package,

- From cultural differences as an obstacle to cultural diversity as opportunity,

- Culture meets psychology, and psychology meets culture.

In identifying the above trends, we have greatly benefitted from the work of Gerd Gigerenzer and his Law of Indispensable Ignorance: The world cannot function without partially ignorant people (Gigerenzer, https://www.edge.org/response-detail/10224). Gigerenzer most impressively showed this in his study on predictions of stock performance: Pedestrians who predicted stock performance merely on the basis of name recognition easily outperformed market experts and the Fidelity Growth Fund and helped Gigerenzer win US$ 50,000 in a bet against the Fund that they would) (Gigerenzer, 2007).

In our discussion of trends, we have therefore listened first to our intuition about what is trending: Which services do clients ask for, what are we discussing among colleagues? Which topics are trending on LinkedIn, Twitter and Facebook? Which questions are addressed in blogs, papers and publications by practitioners and academics? Based on this unsystematic and non-exhaustive evidence, we formed an idea of current trends and where possible, consulted additional sources to check whether we were on the right track.

[nextpage title=”Trend 1: From cross-border business interactions to interactions within culturally diverse societies”]

The fall of the Berlin Wall launched which we now call the era of globalisation: People, organisations and governments communicating, cooperating and competing beyond their national borders. Waves of cross-border M&As, with peaks in 2000 and 2007 (OECD, 2010), alerted decision-makers to the need to understand their counterpart’s cultural logic and expectations. Co-incidentally or not, Hofstede’s (1980) famous study Culture’s Consequences had just been published, offering heretofore unknown efficiencies for capturing differences between countries. The interest in ‘culture’ as something that the other party ‘had’ took off (see Bolten, 2011, for discussion).

TIP

Today, participants seem increasingly sensitive to the risk of stereotyping; increasingly aware that our national culture is only one of our social layers, and increasingly resistant to the idea of rank-ordering countries numerically on cultural dimensions, as is done for example, in Hofstede’s (1980; Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov, 2010) research. Be careful in how you introduce and talk about models of cultural dimensions. To start the discussion in the right direction, you may find Jürgen Bolten’s definition of culture useful, which is summarised in Section 1 ‘What is culture?’

Information about cultural differences alone, however, does not make us interculturally effective – we also need specific intercultural competences. Research on intercultural competences started in the US with the PeaceCorps studies (Pusch, 2006), and the concept fitted well into trends in HR to move from job analysis to competence model development (Voskuijl and Evers, 2008). According to Google’s ngram viewer, interest in intercultural competences has grown exponentially since 1980, and in fact, since 2004, has been attracting more discussion than ‘Geert Hofstede’ attracted citations.

Curious about Ngram Viewer and the search we conducted? Please click here:

Over the past 15 years, interest in ‘diversity’ has been growing immensely. We use quotes to indicate that here, the word is a placeholder for a battery of related terms, including cultural diversity, diversity management, diversity and inclusion, to name just a few. Non-English-speaking countries in Europe may use the English expressions, translations thereof or terms unique to their linguistic, cultural and societal context, for example:

- In Dutch, we find diversiteitsbeleid (diversity policy), omgang met minderheden (dealing with minorities), and persoon met migratieachtergrond (person with a migration background),

- In Germany, diversity management is translated as ‘Umgang mit Vielfalt’: with Vielfalt (literally: many-ness) triumphing over Einfalt (literally: one-ness but meaning stupity). Diversität is usually combined with one or more of the three I’s: Inklusion, Integration and Interkulturalität.

The words used in a society always reflect that country’s unique composition of (non-)dominant groups, unique discussions about inclusion and integration, and unique sensitivities formed by historical, political, economic and organisational factors. The topic has been on the agenda in the United States for decades (Williams and O’Reilly, 1998), whilst Europe, one might say, has been rather slow on the uptake. Today, however, diversity and Diversity & Inclusion (D&I) are also hot topics in many European countries, as is evidenced, for example, by a special D&I issue by the NRC Handelsblad, a major Dutch daily newspaper, published on the day of writing (NRC Handelsblad, 2019).

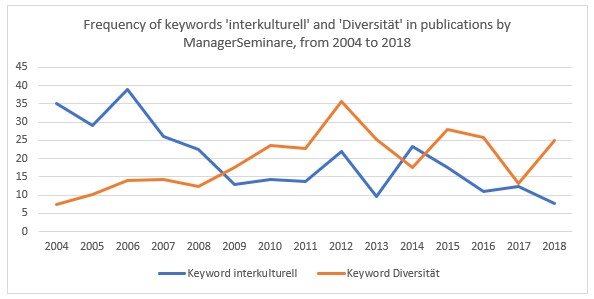

A small analysis further supports our hunch that we are dealing with a trend, a shift in attention from one topic to another: publications from 2004 to 2018 in ManagerSeminare, a German-language journal on training needs and topics (ManagerSeminare, 2004-2018; Lambers, 2019). We searched with the most general keywords ‘interkulturell’ and ‘Diversität’ and calculated the percentage with which each keyword was used along those 15 years. Here is the graph:

POWER AND DIVERSITY

The two major elements discussed under Trend 1 – cross-border business interactions and interactions in culturally diverse societies – can only be understood in relation to dynamics of power inherent to the interaction. For corporate mergers and acquisitions (M&As), power asymmetry is of concern to all stakeholders, with staff worrying about their positions, status and ability to influence as a result of the deal. But interactions between groups in a country bring a more forceful – and often more painful – power dynamic: one group is generally seen as dominant, other groups as non-dominant, with implications for numerous aspects of life and opportunities. An in-country power asymmetry involves a different array of sensitivities for the individuals involved than a power asymmetry in M&As holds for employees. Understanding the local context, developing an antenna for the relations, feelings and tensions between groups is therefore essential when dealing with a culturally diverse classroom.

TIP

When you train in a context where diversity has become salient, familiarise yourself with the proper vocabulary and how members of non-dominant groups prefer to be referred to. To the extent possible, find out about how people feel about the groups involved, and about belonging to a given group. And do not forget your own pre-dominant group affiliation: How does this affect the interaction?

Does Trend 1 imply that interest in cross-border intercultural training will eventually fade out? We do not think so. First, there will always be the need for country-specific culture trainings, e.g., for expatriates and their families. Second, there is a growing need for intercultural training for students preparing for their study abroad (Streitwieser, 2014). Third, there are simply numerous organisations operating across borders which need to get their staff fit for the experience. Cross-border intercultural training is likely to stay. But, as we will discuss next, their role in organisational L&D is likely to change.

TIP

When joining the workforce, many students today will already have lived and studied abroad. The experience is likely to have shaped their view of themselves as culturally savvy and will have influenced how they respond to the topic when it comes up in your training room.

[nextpage title=”Trend 2: Intercultural training: From stand-alone training to being part of a more complex package “]

Supporting people to deal with cultural differences is demanding. How should we introduce ‘culture’ and discuss differences without reinforcing stereotypes? How can we help participants accept that their ideas about people, life and work may not be shared by everybody? How does the group’s composition influence group dynamics? What are differences in learning styles and can we as trainer deal with those?

These demanding stand-alone intercultural trainings have come under pressure. When, after the economic crises in 2001 and 2008, clients started to invest in soft skills training again, fewer of them were interested in intercultural trainings. And if they are today, they allot less time for it than before. Moreover, clients have come to resist words like ‘intercultural’ as too soft and ‘cultural differences’ as too harsh. One important reason behind the changed reception of intercultural training is, we believe, the lacking link between training and effect (Mazziotta, Piper and Rohman, 2016). It is tremendously difficult, certainly for an individual trainer, to demonstrate how intercultural learning makes people interculturally more effective (Salzbrenner, Schulze and Franz, 2014). Knowledge about methods with proven effectiveness is spreading only slowly (Mazziotta, Piper and Rohman, 2016). The missing link between interventions and performance demands may have made clients more sceptical of intercultural training than before.

At the same time, after three decades of globalisation, increased migration and 68.5 million forcibly displaced people world-wide (UNHCR, 2019), societies and organisations must be able to deal with culturally diverse groups. Decision-makers are involved on a daily basis in international projects, they experience first-hand the complexities of multicultural teams, of integrating top talent from abroad, and they are looking for solutions: fresh applications of intercultural insights and skills that help them deal with issues that are measurable for them. The better intercultural topics are integrated with these general business topics, the more popular they will be.

CHECK

What is your area of expertise in VET, and how could you broaden your offering by teaming up with the right intercultural professional?

[nextpage title=”Trend 3: From cultural differences as an obstacle to cultural diversity as opportunity”]

Today, we look at diversity as not just a moral issue, but a business issue. It is a proven fact that diverse companies perform at least 35% better than their homogeneous counterparts (Showers, 2016).

If any of our four trends is supported empirically, it is this one. Take the Journal of International Business Studies (JIBS), one of the major journals in its field. Günther Stahl and Rosalyn Tung analysed all 1141 JIBS articles published between 1989 and 2012 and identified 244 articles that discuss how culture affects business (Stahl and Tung, 2015). Most of these articles present culture as an obstacle to the smooth running of business:

- Of 108 theoretical papers, 69% focus on negative implications, 27% discuss mixed outcomes and only 4% expect positive effects of culture on business, a stunning 17:1 ratio in favour of negative assumptions,

- Of 136 empirical papers, 75% predict negative impact, 20% mixed and only 5% positive effects, a ratio of 15:1. Actual outcomes of these studies, in contrast, suggest a much more positive or at least a mixed picture.

In 2017, Stahl and colleagues devote an entire edition of Cross Cultural & Strategic Management (CCSM) to developing a more balanced, more positive view of culture’s impact on business Stahl et al, 2017). Only a year later, in their 2018 review of research on cross-cultural interaction, Nancy Adler and Zeynep Aycan likewise conclude that it is time to look on the bright side of culture’s influence on organisational behaviour (Adler and Aycan, 2018).

A two-hour search on the internet reveals that this message has been taken on board with full force (19 May 2019). Leading business magazines and research companies like HBR, Forbes and Boston Consulting Group publish material on the innovative power of (culturally) diverse teams. On their websites, 10 of the largest companies in Europe – Shell, Volkswagen, British Petroleum, Santander, Allianz, Total, Daimler, Nestlé, BNP Parisbas and HSBC – all express their appreciation of (cultural) diversity.

Why then has ‘cultural diversity’ had such a fast ride to glory, and what has taken ‘cultural differences’ so long? One reason may be that when we speak of diversity, we look inside, at our own group, and how we all differ from one another: I too am different and therefore unique, but I am still part of a larger whole. When we speak of differences, in contrast, we look at the other group, and how ‘they’ differ from ‘us’ – an unconscious mental move that gets us caught between feeling good about our own group and wanting to be fair and balanced towards other groups.

Trend 3 is a strong one. Culture is no longer seen as just causing clashes and conflict. Instead, by piggybacking on diversity (and diversity’s clear legal implications), ‘culture’ is now more and more seen as an opportunity: to understand the needs of an international and diverse client base; to bring people together internally, and to leverage the innovative potential of teams.

SELF-CHECK:

- Draw a picture of the network of colleagues and associates with whom you work. How diverse is your network and team?

- How do your clients talk about (cultural) diversity? Where on the below spectrum do you see them deal with the topic: Clashes and conflict – legal necessity – a matter of fairness – an opportunity to better understand our clients – a competitive edge for innovation in teams?

How could you support them to recognise the benefits?

[nextpage title=”Trend 4: Culture meets psychology and psychology meets culture”]

The intercultural field is zooming in ever more closely on the individual, while psychological research is zooming out to get culture into focus.

We will start with Jürgen Bolten’s New Thinking, move on to unconscious bias and halt at cultural neuroscience. Then we will zoom out, from WEIRD people to cross-cultural psychology. Each topic is like a sign on a door behind which is a world of ideas, and we hope that Trend 4 will make you feel like knocking on these doors and demanding entry. We will end by an outlook on where Trend 4 may bear important fruit for intercultural training.

Picture by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash

[nextpage title=”Culture meets psychology: New Thinking “]

How do we need to think about ‘culture’ if we want to support our clients in being more effective in their intercultural interactions? In two papers published in Interculture Journal, Bolten captures major shifts in thinking about cultural influences on individuals and groups, and what these shifts eventually imply for conducting intercultural training (Bolten, 2011, 2016). Bolten argues that with each shift in thinking, ‘culture’ is seen more as a dynamic factor influencing individuals and situations, and less as a set of fixed properties of groups. The early ways of thinking about culture focused on differences between homogenous groups, who upon contact would easily experience clashes and conflicts (see also Trend 3). Today, we are invited to see ourselves as belonging to multiple groups, and to relate to others by jointly exploring the groups to which we belong, and what this means for our interaction (Rathje, 2007). In this New Thinking paradigm, classic dimensions of cultural differences (e.g., power distance, individualism) and diversity management (e.g., gender, ethnicity) help us to better understand how we have been influenced, and to mindfully relate to others based on our multiple group memberships.

The New Thinking paradigm offers many fruitful connections to the Social Identity Approach in social psychology (see Brown, 2000, for a review). The Social Identity Approach analyses how we develop a sense of self, based on categorising ourselves and others in terms of our various group memberships. It builds on two major theories: social identity theory formulated by Henri Tajfel and John Turner (Tajfel and Turner, 1979) and self-categorisation theory developed by John Turner and colleagues (Turner et al 1987). Self-categorisation theory describes when and how we consider a mere collection of individuals to form a meaningful group, and what happens when we do so. Social identity theory focuses on those layers of our identity that stem from our various group memberships (I am a VET trainer; I am a Bavarian); and on how we interact with others depending on whether we perceive each other as belonging to the same group (e.g., fans of Bayern München) or to different groups (Bayern München versus Ajax), and depending on the status we feel our groups deserve (which here may be sorted by the European Championships). The theory also addresses whether we consider status differences to be legitimate and changeable (see you at the next Championship!), and the extent to which we can change group membership (impossible for most fans, conceivable for Arjen Robben).

Photo by Susan Yin on Unsplash

Importantly, social behaviour moves along a continuum of exclusively interpersonal behaviour at one end, and exclusively intergroup behaviour at the other end. The most extreme form of intergroup behaviour implies that we only see others as interchangeable members of a group, dehumanising each other with all well-known potential consequences. The New Thinking approach and the social identity approach offer, alone and together, many new roads and fresh ideas for improving intercultural training.

[nextpage title=”Culture meets psychology: Unconscious bias”]

A friend of ours was alone in the IT room of the company she worked for. The door swings open and a senior officer peeks inside, his eyes passing over her; he mumbles ‘ah nobody in here’ and disappears.

How can we use knowledge about psychological functioning to help our clients be more accurate when observing, interpreting and evaluating others across the in-group / out-group divide? Unconscious bias refers to cognitive mechanisms that distort our judgement in favour of one group of people over another.

To learn about the way in which stereotypes reduce our perception of others, visit Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Ted Talk ‘The danger of a single story’:

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The danger of a single story

The King of All Biases is the Similarity Attracts bias – the tendency to like and to consider competent people who are like us. This affects the partners we choose for life, and the candidate we choose for board membership. Click here to see its effects at South Park: https://youtu.be/7u7kpr5kehY

Unconscious biases (there are many) mostly work in favour of the dominant group in a society or organisation, i.e., the group that is privileged in terms of access to people and resources, and against non-dominant groups, for whom access is restricted. Unconscious biases have become notorious for how they influence power holders in organisations in decisions about recruitment, promotion and performance management.

Unconscious biases reveal how difficult it is for us to correctly perceive, interpret, evaluate and remember each other in terms of competences, motivations and motives, with severe implications for people’s opportunities in life and at work. We are, however, usually unconscious of these biases, can become aware of them and ultimately overcome them. This is the goal of Unconscious Bias trainings, which have become popular (see Lai et al, 2014, for a review). Designing and delivering unconscious bias training may seem easy. When doing so, however, trainers should beware of the self-serving bias. Raising awareness of biases may not be enough for people to overcome their biases; instead trainers may unwillingly reinforce the very stereotypes their intervention was supposed to overcome (Noon, 2018).

[nextpage title=”Culture meets psychology: Cultural psychology and cultural neuroscience”]

How does culture influence individuals in thought, emotion and behaviour? This is the core question of cultural psychology (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). Cultural psychology makes captivating assumptions about culture’s influence on individuals and uses methods of psychology to test the assumptions. In their ground-breaking review, Markus and Kitayama (1991) discuss numerous differences in thought and behaviour, explaining these mainly by a difference between cultures stimulating an independent versus an interdependent sense of self. (This distinction is closely related to the cultural dimension individualism and collectivism, and it usually entails comparisons between European Americans/Europeans with East Asian cultural groups.)

One study focuses on differences between the North and the South of the USA (Nisbett and Cohen 1996). Using historical, archival and recent experimental data, Richard Nisbett and Doy Cohen (1996) explain higher degrees of violence among white males in the South compared to the North by a culture of honour. The culture of honour demands that a man be highly responsive to any potential affront, because his reputation of strength and fearlessness is essential for his and his family’s economic survival. Why a culture of honour in the South, and not in the North of the US? Because large groups of settlers arriving in the South from 1700 onward came from regions in Ireland and Scotland so barren that they only allowed for herding, not farming. Unlike farms, herds can be stolen so herders need to demonstrate to potential attackers that attacking them is not a good idea. Take a moment to digest this: Nisbett and Cohen provide evidence that culture can influence us three centuries after we collectively change continent!

Tip: The next time your participants ask whether cultures are not all merging into one at this day and age (so why bother learn about the differences?), pull out your copy of Nisbett and Cohen’s (1996) Culture of honor.

How can we dig deeper in our efforts to understand how culture influences individual psychological functioning? Cultural neuroscience is the delta where cultural psychology merges with another major stream of research, cognitive neuroscience. Put briefly, cognitive neuroscience offers its tools of tracking brain activity to analyse the potential interplay between cultural differences in thought and behaviour, and brain structures and processes. Cultural neuroscience is a vast and rapidly growing field of research. An excellent overview of major topics, findings and methodological issues raised by other authors, has been provided by Rule (2014).

[nextpage title=”Psychology meets culture: WEIRD people and transnational (feminist) psychology”]

How can we do better research by stopping to work only with subjects from similar socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds? WEIRD is an acronym for Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic, referring to the undergraduate students who typically take part in psychological research. The WEIRD acronym was introduced by Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan (2010) in a meta-analysis of research that immediately made it to the Hall of Fame in psychology. Their study brought what had long been vaguely acknowledged to public attention: that claims about psychological phenomena (from visual perception to romantic love) may be premature since they usually rest on research involving subjects who represent not more than 15% of the human population.

For a short interview with Joseph Henrich, please click here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5RxKitXHyc

How do we need to do research if we want to take the effects of historical and current power inequalities between cultural groups seriously? This is the quest of transnational (feminist) psychology, which calls upon researchers to consider how institutions have been shaped by colonisation, imperialism and globalisation when designing and conducting their research studies.

[nextpage title=”Psychology meets culture: Cross-cultural psychology”]

How can we seize the opportunities for more interesting research that cultural variation offers, and how can we better understand cultural influences on individuals, by rigorously reflecting on the methods we use? Cross-cultural psychology studies human behaviour and mental processes by paying explicit attention to the diversity of cultural conditions that have evolved (Berry and Poortinga, 2011; Berry et al 2011). Cross-cultural psychology as a field has steadily grown in importance over the past five decades; by now, an ever-increasing number of studies incorporate cultural and diversity factors from the outset in their research design.

The earlier discussed cultural psychology holds that cultural differences influence human thought and behaviour so strongly that any search for universally valid psychological phenomena has to be futile. Cross-cultural psychology, in contrast, encourages both research on culturally unique aspects of human functioning, and research on potentially universal aspects. In line with the WEIRD wake-up call and transnational psychology, cross-cultural psychology aims to reduce ethnocentric (Western) biases in psychological research. But it goes beyond these in that it combines analyses of cultural and individual differences and similarities with a rigorous scrutiny of the psychological toolbox. Cross-cultural psychology has also been described as “a type [of] research methodology, rather than an entirely separate field within psychology” (Lonner, 2000, p. 22) and it is becoming more and more successful in making psychology meet culture.

[nextpage title=”In conclusion”]

Trend 4 holds enormous promise. It stimulates our curiosity about how cultures influence individuals, and how individuals influence culture. But it also reminds us that it is time to scrutinise the intercultural toolbox in order to determine which training methods are effective, and when a given method should be applied. Intercultural and diversity interventions are complex and demanding. We hope that Trend 4 will help pave the way for training methods that are both theoretically sound and empirically tested (Mazziotta, Piper and Rohmann 2016).

[nextpage title=”Quiz”]

[nextpage title=”References”]

Adler, N.J. and Aycan, Z. (2018) ‘Cross-cultural interaction: What we know and what we need to know’, Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, p307-333.

Berry, J. W. and Poortinga, Y. H. (2011) Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berry, J.W., Poortinga, Y.H., Breugelmans, S.M., Chasiotis, A. and Sam, D.L. (2011) Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bolten, J. (2011) ‘Diversity Management als interkulturelle Prozessmoderation’ (Diversity management as intercultural process moderation), Interculture Journal, 10(13), p13-38.

Bolten, J. (2016) ‘Interkulturelle Trainings neu denken‘ (Rethinking intercultural trainings), Interculture Journal, 15(26), p75-91.

Bolten, J. (2016) ‘Interkulturelle Trainings neu denken’ (Rethinking intercultural trainings), Interculture Journal, 15(16), p75-91.

Brown, R. (2000) Social Identity Theory: past achievements, current problems and future challenges. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30(6), p745–778.

Desjardins, J. (2017) Every Single Cognitive Bias in One Infographic [Online]. Available at

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/every-single-cognitive-bias/ (Accessed 1 August 2019)

Gigerenzer, G. (2007) Gut Feelings. The intelligence of the unconscious. New York: Viking.

Gigerenzer, Gerd (2004) ‘Gigerenzer’s Law of Indispensable Ignorance’, The Edge [Online]. Available at: https://www.edge.org/response-detail/10224 (Accessed 8 May 2019)

Henrich, J., Heine, S.J. and Norenzayan, A. (2010) ‘The weirdest people in the world?’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), p61-83.

Hofstede, G. (1980) Culture’s consequences. International differences in work-related values. 1st edn. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J. and Minkov, M. (2010) Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. 3rd edn. New York: McGraw Hill.

Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking: Fast and slow. London: Penguin Books.

Kurtis, T. and Adams, G. (2015) ‘Decolonizing liberation: Toward a transnational feminist psychology’, Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3(2), p388–413.

Lai, C.K. Marini, M., Lehr, S.A., Cerruti, C., Shin, J.-E.L, Joy-Gaba, J.A.and Nosek, B.A. (2014) ‘Reducing implicit racial preferences: I. A comparative investigation of 17 interventions’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(4), p1765-1785.

Lonner, W. J. (2000) ‘On the growth and continuing importance of cross-cultural psychology’, Eye on Psi Chi, 4(3), p22-26.

managerSeminare. Available at https://www.managerseminare.de (Accessed: 8 May 2019)

Lambers, S. (2019) ‘Ausblick auf die Trends von morgen: Transformation der Arbeitswelt‘, managerSeminare, 251 [online]. Available at: https://www.managerseminare.de/ms_News/Transformation-der-Arbeitswelt-Ausblick-auf-die-Trends-von-morgen,269235 (Accessed: 8 May 2019)

Markus, H.R. and Kitayama, S. (1991) ‘Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation’, Psychological Review, 98(2), p224-253.

Mazziotta, A., Piper, V. and Rohmann, A. (2016) Interkulturelle Trainings: Ein wissenschaftlich fundierter und praxisrelevanter Überblick. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Nisbett, R.E. and Cohen, D. (1996) New directions in social psychology. Culture of honor: The psychology of violence in the South. Boulder, CO, US: Westview Press.

Noon, M. (2018) ‘Pointless Diversity Training: Unconscious Bias, New Racism and Agency’, Work, Employment and Society, 32(1), p198–209.

NRC Handelsblad (2019) ‘Inclusiviteit op de werkvloer’ (Inclusion at work) [Online], NRC Handelsblad (Weekend edition), 18 May 2019. Available at https://www.nrc.nl/dossier/inclusiviteit-op-de-werkvloer/. (Accessed 1 August 2019)

OECD Publishing (2010). Cross-border mergers and acquisitions. In Measuring Globalisation: OECD Economic Globalisation Indicators 2010. Paris, France.

Pusch M.D. (2004) ‘Intercultural Training in Historical Perspective’ in Landis, D., Bennett, J.M. and Bennett, M.J. (eds), Handbook of intercultural training. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, pp. 13-36.

Rathje, S. (2007) ‘Intercultural competence: The status and future of a controversial concept’, Language and Intercultural Communication, 7(4), p254-266.

Rule, N.O. (2014) ‘Cultural Neuroscience: A Historical Introduction and Overview’, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 9(2).

Salzbrenner, S., Schulze, T. and Franz, A. (2014) A status report of the intercultural profession [Online]. Available at https://www.academia.edu/10617932/A_status_report_of_the_Intercultural_Profession_2014. (Accessed 1 August 2019).

Showers, R. (2016) ‘A Brief History of Diversity in the Workplace’ [Online]. Available at https://www.brazen.com/ (Accessed 8 May 2019)

Stahl, G.K. and Tung, R.J. (2015) ‘Towards a more balanced treatment of culture in international business studies: The need for positive cross-cultural scholarship’, Journal of International Business Studies, 46(4), p391-414.

Stahl, G.K., Miska, C., Lee, H.-J. and Sully De Luque, M. (2017) ‘The upside of cultural differences: towards a more balanced treatment of culture in cross-cultural management research’. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 24(1), p2-12.

Streitwieser, B. (2014) Internationalization of Higher Education and Global Mobility. Oxford Studies in Comparative Education. Oxford, UK: Symposium Books.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J.C. (1979) ‘An integrative theory of intergroup conflict’ in Austin, W.G. and Worchel, S. (eds). The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole, pp. 33-48.

Turner, J.C., Hogg, M.A., Oakes, P.J., Reicher, S.D., Wetherell, M.S. (1987) Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell.

UNCHR The UN Refugee Agency (2019) Figures at a glance [Online]. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html (Accessed 98 May 2019)

Voskuijl, O.F. and Evers, A. (2008) ‘Job analysis and competency modelling’ in Cartwright, S. and Cooper, C.L. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Personnel Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 139-163.

Williams, K.Y. and O’Reilly, C.A. (1998) ‘Demography and diversity in organizations: A review of 40 years of research’, Research in Organizational Behavior, 20, p77-140.

Recent Comments