[nextpage title=”Introduction”]

This module examines concepts of culture that capture its highly nuanced, multi-dimensional and dynamic nature. Three recent approaches will be presented which are particularly meaningful because they focus on the multi-dimensional nature of culture. It will start with an early definition of culture, explore where the concept of culture comes from, and then introduce the three recent approaches in more detail.

By the end of this module, you will have learned about:

- culture as complex social construct

- the definition of “world culture” of Hannerz, and his thoughts on how local and global cultures are connected

- the “fuzzy culture” approach of Bolten, and his concept of intercultural competence

- the UNESCO focus on culture as creative diversity, and its concept of “culture identity”

Source: https://pixabay.com/it/photos/libri-porta-ingresso-cultura-1655783/

When defining the term “culture”, it is useful to contrast “culture” and “a culture”, first proposed by the anthropologist Margaret Mead in the late 1930s: “Culture means the whole complex of traditional behaviour which has been developed by the human race and is successively learned by each generation.” […] “A culture is less precise. It can mean the forms of traditional behaviour which are characteristic of a given society, or of a group of societies, or of a certain race, or of certain area, or of a certain period of time”. (Mead, 2002).

The model of culture proposed by the anthropologist Ulf Hannerz is the first one we will present in greater detail. Hannerz considers national understanding of culture as insufficient in an ever-more interconnected world. From his perspective, there is now a world cultural framework which is created through the increasing interconnectedness of varied local cultures, as well as through the development of cultures without a clear anchorage in any one territory.

The second model is the “fuzzy culture” approach by Jürgen Bolten, who describes a multi-perspective observation of interaction between differently socialised persons. Bolten developed a model of intercultural action competence which considers the effective integrated interaction between personal, social, methodological and professional competence in an intercultural context.

The third model is the UNESCO model of cultural identity, which is considered as a fluid, self-transforming process, best understood as a future project rather than in terms of past inheritance. For UNESCO, in a global world, cultural identities derive from multiple sources; the increasing plasticity of cultural identities reflects the growing complexity of the global flows of people, goods and information.

[nextpage title=”Culture as a social construct”]

Culture is a social construct, and it is generally considered highly subjective. Etymologically, the word derives from the Latin root-term “colere”, which means to inhabit, to cultivate or to honour; the root-term generally refers to patterns of human activity and the symbolic structures that give commonly-agreed meanings to such activity.

In its broader sense, the term “culture” refers to the systems of knowledge shared by a relatively large group of people who develop a common series of cultivated behaviours, which correspond to the totality of a person’s learned, accumulated experience.

Culture is socially transmitted, in the sense that behaviours pass between generations through social learning. During this inter-generational transmission, culture might acquire new behaviours, confirm or modify the previous ones, as it refers to the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, hierarchies, religion, notions of time, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe, material objects and possessions acquired by a group of people in the course of generations through individual and group striving.

Culture includes shared communicative symbols, some of which represent a group’s skills, knowledge, attitudes, values and motives. The meanings of the symbols are learned and deliberately perpetuated in a society through its formal and informal institutions.

Socially, culture consists of explicit and implicit patterns and behaviour acquired and transmitted by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievement of human groups, including their embodiments in artefacts; the essential core of culture consists of traditional ideas and their attached values; culture systems may, on the one hand, be considered as products of action, and on the other hand, as conditioning influences upon further action.

Social groups constantly create and recreate the behavioural patterns that define a culture. At the same time, the term culture is used in a variety of very different contexts in our society. Today, the term is not only used to describe fine arts, but also to describe social groupings and their behavioural patterns.

Culture is a collective common-ground that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another.

With such a broad usage, culture may be misused in order to label people, to justify lack of understanding, and to claim that attempts at understanding must always be futile because of presumed insurmountable differences between cultural groups. Sentences such as “we are from different cultures”, implicitly excluding others from one’s own group, may easily invite this kind of thinking. “Culture” may also be used to explain a variety of misunderstandings or differences which in fact would be more accurately explained by differences in age, socialisation, language, gender and/or status, and which moreover could have been prevented with better communicative skills and bigger efforts to understand each other.

For the reasons stated above, in this module, we will promote definitions of culture that emphasise its highly nuanced, multi-dimensional, and dynamic nature.

Source: https://pixabay.com/it/photos/migrazione-integrazione-migranti-3129340/

[nextpage title=”Culture in an interconnected world: the approach of anthropologist Ulf Hannerz “]

The anthropologist Ulf Hannerz set out to expand any national understandings of culture, which he considers to be insufficient in an ever-more interconnected world. From his perspective, there is now a world cultural framework which is created through the increasing interconnectedness of varied local cultures, as well as through the development of cultures that are not anchored in any one territory.

Hannerz proposes that local cultures can today be more accurately seen as sub-cultures within a wider whole; as cultures which need to be understood in the context of their cultural surroundings rather than in isolation. He examines the process of local absorption of global cultural flows and the mix between global and local cultural elements, and shows that the global cannot exist without the local. Between these two levels, people may have worked out a whole range of ways of relating to today’s global interconnected diversity of cultures.

The essential elements of the local can be found in local daily life-world, which Hannerz calls the “form-of-life context”. The framework includes daily activities at home, at work, and in the neighbourhood, daily emotionally relevant face-to face relationships with other people in the region, and daily uses of symbolic forms, in short, all those elements that last long and are part of the local life (Hannerz, 1996). The events and experiences of local everyday are considered to be direct and genuine. Often, these elements greatly impact on people’s lives, continuously producing and reproducing “culture”.

Consequently, it is at the local level where global influences are filtered, transformed and incorporated into beliefs and practices. Hannerz thus considers the local daily life-world as the area where global cultural elements, and those symbolically located in a different local world, have a chance of making themselves at home.

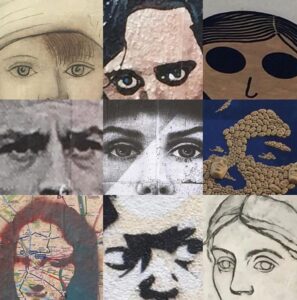

Source: https://pixabay.com/it/photos/graffiti-strada-persone-cultura-3305166/

[nextpage title=”Bolten’s fuzzy culture approach “]

The “fuzzy culture” approach of Bolten describes a multi-perspective observation of the interaction between differently socialised persons. He affirms “cultures cannot be clearly bordered; their edges appear, rather, as a confluence of diverse transcultural networks. Cultures are inherently uneven, or fuzzy” (Bolten, 2014).

Bolten emphasises that the identity of persons is defined by their affiliation with several groups, for example, family, ethnicity, religion, vocational world, and also virtual communities.

Source: Creative Commons by Paolo Brusa cc s.a

Bolten describes intercultural competence as the effective integrated interaction between individual, social, strategic and professional competence in an intercultural context. “Intercultural competence” must therefore be understood as a process, and not a static phenomenon that can be limited to unchanging personal and social clues sometimes referred to as “soft skills”

Bolten’s model of intercultural action competence combines two structural systems of intercultural competence in a matrix with the following categories:

(a) three dimensions: knowledge, behaviour and attitude

(b) four competence categories: individual, social, strategic and professional (active competence).

Bolten proposes to combine the dimensions knowledge, behaviour and attitude with the competence categories individual, social, strategic and professional, arriving at a concept of intercultural competence that reflects the individual, social, strategic and professional aspects of the competence:

- characteristics like “openness”, “flexibility”, or “cultural awareness” would represent features of individual competence

- “intuition” and “ability to communicate” would be seen as aspects of social competence,

- “having realistic expectations” as reflecting aspects of methodological competence.

As the process model accounts for the influence of methodological and professional competence (for example, strategy and expertise) as well as for social and personal competences, the resulting interplay between these competence categories includes the factors known as “hard and soft factors” in human resource development circles.

Therefore, one can be considered “interculturally competent” when one is aware of and able to effectively balance personal, social, methodological and professional criteria in an intercultural environment. Intercultural competence also requires the establishment of effective synergies between the foreign culture and one’s own culture. This balancing act between the foreign and the familiar might include the active negotiation and implementation of one’s own communicative habits, but the idea of “balance” does not only mean that all four of the integral competencies must be present in equal amounts. It also means that “intercultural competence” is never a universal concept that can be defined outside of situational or cultural specifics.

[nextpage title=”UNESCO definitions of culture and cultural identity “]

The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) defines culture as a “set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual, and emotional features of society or a social group, and that it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs.” (UNESCO, 2011).

This definition allows for two different but complementary interpretations of culture. First, culture is the creative diversity embodied in particular “cultures” (in the plural), with their unique traditions and tangible and intangible expressions. Second, culture (in the singular) refers to the creative impulse that lies at the heart of that diversity of “cultures”.

The two meanings of culture – one self-referential, the other self-transcending – are inextricably linked and provide the key to envisioning the fruitful interaction of peoples in the context of globalization.

One of the fundamental obstacles to intercultural dialogue is the habit of the conceiving of cultures as fixed entities, as if fault-lines separated them. Cultures, however, are not self-enclosed or static entities. Dialogue between cultures becomes easier if we think of cultures as having porous boundaries holding the creative potential of the individuals they encompass. Cultures, like individuals, exist in relationship to one another.

Source: https://pixabay.com/it/photos/afghanistan-citt%C3%A0-persone-mercanti-79492/

[nextpage title=”To sum up”]

The above definitions of culture highlight dynamic and relational, multi-dimensional, and expansive conceptualisations of culture.

The first definition captures the liquid flexibility and variability of modern and post-modern life-style, where the increasing interconnections of varied local cultures meets the development of cultures without a clear anchorage in any one territory.

The second definition suggests a more expansive and inclusive view of culture, based on a focus which includes the individual perspective observation of the interaction between differently socialised persons.

The final definition emphasises culture’s existence as a variable and fluid construct, both on a group and individual level where the relative perspective of the observation marks the final statements.

The UNESCO stresses the importance of understanding cultures not as “self-enclosed or static entities”, introducing the difference between “culture” and “sub-culture”, and linking any possible definition to the common ground of basic human rights.

UNESCO rather suggests to consider cultures as clouds, with “their confines ever changing, coming together or moving apart … and sometimes merging to produce new forms arising from those that preceded them, yet differing from them entirely … Culture is the very substratum of all human activities, which derive their meaning and value from it” (UNESCO; 2011).

Source: Photo by Billy Huynh on Unsplash

- We understand culture as a complex social construct.

- There are many definitions of culture and ways to use the term.

- Every person belongs to multiple cultures.

- Cultures overlap and are connected in a fluid network of belongings and attributions.

- Cultures include, but are not limited to national culture.

- Even though cultures might seem homogeneous from the outside, they are in fact always made up of unique individuals and thereby heterogeneous.

[nextpage title=”Quiz”]

[nextpage title=”References”]

Axelrod, R. (1997) ‘The dissemination of culture: A model with local convergence and global polarization’, The Journal of Conflict Resolution, p. 41.

Bailey, G. and Peoples, J. (1998) Humanity: an introduction to Cultural Anthropology. St. Paul, MN: West Pub. Co.

Bolten, J. (2012) Interkulturelle Kompetenz. Erfurt: Thüringer Landeszentrale für politische Bildung.

Bolten, J. (2014) The Dune Model – or: How to Describe Culture. New York: icNew Link.

Hannerz, U. (1992) Cultural Complexity: Studies in the Social Organization of Meaning. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hannerz, U. (1996) Transnational Connections: Culture, People, Places. London: Routledge.

Hofstede, D.G. (2001) Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. 2nd edn. London: Sage Publications, Inc.

Keesing, R.M. ( 1981) Cultural anthropology: A contemporary perspective. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Kroeber, A.L. and Kluckhohn, C. (1952) ‘Culture: A critical review of concepts and definitions’. Papers of the Peabody Museum, p. 47.

Mead, M. and Mètraux, R. (1952) The Study of Culture at a Distance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mead, M. (2012) Cooperation and Competition Among Primitive Peoples. New York: Transaction Publishers.

Schuerkens, U. (2017) Social Changes in a Global World. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications.

Turner, V. W. (1975) Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society (Symbol, Myth, & Ritual). New York: Cornell University Press.

Unesco (2001) Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. Online available at http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/pdf/5_Cultural_Diversity_EN.pdf (Accessed 1 August 2019).

Recent Comments